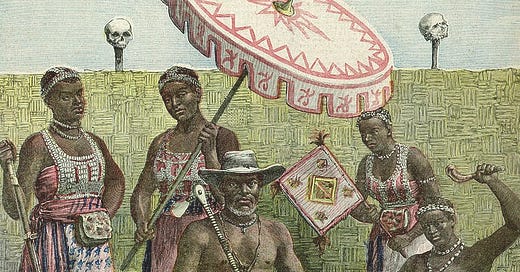

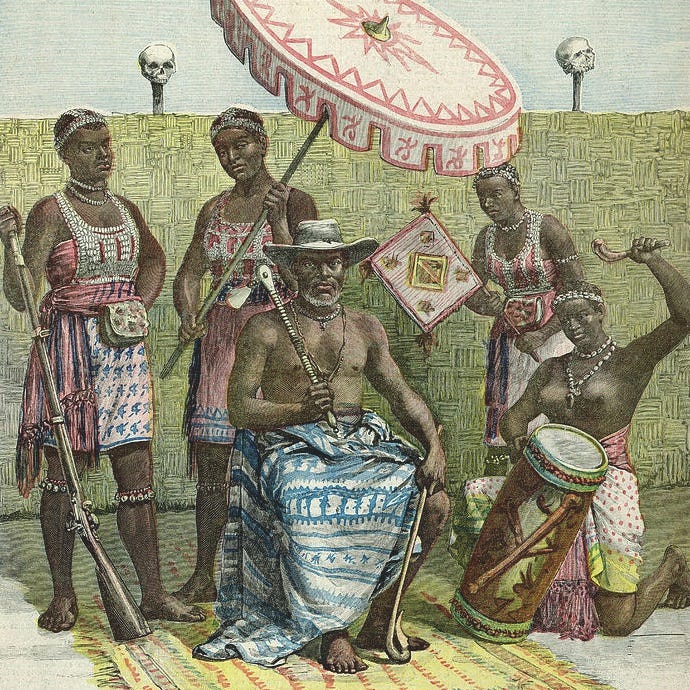

The Warrior Queens of Dahomey

In 2022, Hollywood put out a movie called “The Woman King”, which was (very loosely) based on female warriors in 19th century West Africa. I haven’t seen the movie, but I am sure it takes huge liberties with the truth. (The name alone is ridiculous.) But I haven’t seen it, so I won’t critique it. Instead, I’ll just talk about the historical reality on which it is supposedly based: the Kingdom of Dahomey and its female warriors.

The Kingdom of Dahomey existed from about 1625 to 1904, in what is now Benin. It did have female warriors, the Agojie. These feminist icons were the third-class wives of the king, judged too ugly for him to have sex with:

As Alpern told Smithsonian magazine in 2011, the Agojie were considered the king’s “third-class” wives, as they typically didn’t share his bed or bear his children. Because they were married to the king, they were restricted from having sex with other men, although the degree to which this celibacy was enforced is subject to debate. In addition to enjoying privileged status, the warriors had access to a steady supply of tobacco and alcohol. They also had enslaved servants of their own.

Source: The Real Warriors Behind ‘The Woman King’.

In Dahomean society, women were the property of men. The king had his pick of the young women of the kingdom, marrying any that he chose. The warrior queens were queens, in the sense that they were officially wives of the king. They were expected to be celibate, because they were the sexual property of the king, but he did not waste his precious sperm on them.

The origin of warrior queens is probably from a harem guard. The king would not trust men to guard his harem, naturally. So, he used women instead.

Due the the incessant warfare necessary to obtain slaves for sale and sacrifice, the male population of the kingdom declined, and the female palace guard expanded and became a military force.

Their main occupation was not defending their kith and kin from external enemies. It was slave-raiding. They would march a long distance in secrecy to attack a village at night. They would capture the young and healthy, who could be sold, and massacre everyone else. Some unsalable people would also be taken for human sacrifice.

Perhaps “The Woman King” is based on Nanisca, described here:

In 1889, French naval officer Jean Bayol witnessed Nanisca (who likely inspired the name of Davis’ character in The Woman King), a teenager “who had not yet killed anyone,” easily pass a test of wills. Walking up to a condemned prisoner, she reportedly “swung her sword three times with both hands, then calmly cut the last flesh that attached the head to the trunk. … She then squeezed the blood off her weapon and swallowed it.”

Source: The Real Warriors Behind ‘The Woman King’.

In this scene, the girlboss warrior isn’t bravely defending her people from enemies. She is cutting the head off a defenseless captive, probably captured during a slaving raid and judged unfit for sale.

The kingdom of Dahomey was dependent on the slave trade. This trade did not benefit the ordinary people of the kingdom very much, if at all. But it did benefit the elite. They could trade human captives for guns, which they could use to maintain their power structure and capture more slaves.

A similar pattern occurred in many places where Europeans interacted with more primitive societies. Native political units would often try to monopolize trade with Europeans, and use the weapons acquired by trade to conquer, enslave, massacre, and rape other native people. The Musket Wars between the Maori in New Zealand is a good example.

It’s not that Europeans somehow forced native people to fight each other. People have always fought each other, in every part of the world. European trade gave native people living in certain places a temporary advantage over other natives. This upset the existing balance of power, allowing some tribes to win at the expense of others, but it had little effect on the total body count from warfare. Primitive societies are not peaceful utopias.

Mass human sacrifice was an important ritual in Dahomey. Every year, the “Annual Customs” were held. This was a political and religious ceremony that involved displays of wealth and human sacrifice, called “watering the graves”. Slaves and/or criminals would be killed to water the graves of elite ancestors.

To water the grave of his father, the king Glele (also known as Badahung or Badaho) sacrificed 800 captives in the annual customs.

In 1860, two years after the death of King Gezo, his son, King Badahung, the new King of Dahomey decided that in honour of his father’s memory, a “grand custom” must be made. A “grand custom” was the ceremonial sacrifice of hundreds of slaves. A pit was dug in order to collect enough blood to float a canoe. Some 2,000 persons were to be sacrificed, they were to be beheaded and thrown into the pit to bleed out.

Source: 800 Slaves Sacrificed in Tribute on the Death of GEZO the Great Slave King of Dahomey 1858.

Only 800 were sacrificed, perhaps because Glele couldn’t capture enough people, and also because he sold some of his captives as slaves.

In a treaty with Dahomey, Queen Victoria insisted that her subjects not be required to attend the annual customs and witness human sacrifice.

By 1877, Queen Victoria had succeeded in signing a new treaty with the Dahomey which replaced the one she had signed with the slave-hunter King Gezo. Despite an 1852 provision to abolish the slave trade in Dahomey, slave hunting continued well after Gezo and his son Badahung.

One important provision in the treaty of 1877 was that no British subject was compelled to watch any more public human sacrifices!

Source: 800 Slaves Sacrificed in Tribute on the Death of GEZO the Great Slave King of Dahomey 1858.

Will Hollywood ever make a movie about the reality of Dahomey or the West African slave trade?

I doubt it.

February is “Black History Month”, which is not about real history, but about sacralizing black people. It is about constructing myths. Real history is accurate knowledge of the past. We should try to understand the reality of the past, not construct myths that are rooted in current moral fashions.

We need a “Real History Month”.